It’s a question that’s often asked. Who was supposed to succeed King Edward the Confessor when he died on 5th January 1066? For most people, it’s a choice between Harold Godwineson and William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy. Let’s have a look at their respective cases.

Harold, in his forties in 1066, was the most powerful figure in all England after the king. He was Earl of Wessex, holder of vast tracts of land and also had the support of two more brothers – Gyrth and Leofwine – who also held earldoms in England. On top of this, he was a proven war leader, a successful general. Small wonder then that he might wish to take the place of the childless Edward when the time came.

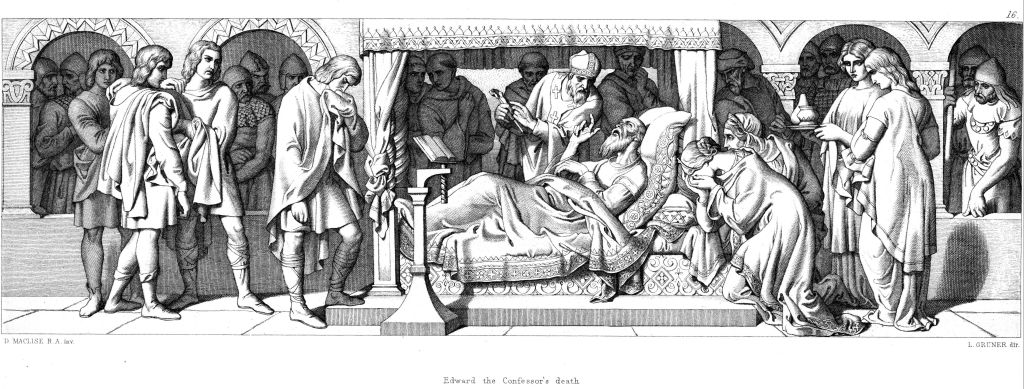

And by virtue of a great piece of opportunism (i.e. being closest to Edward when he breathed his last), he was able to claim that the dying king had bequeathed the the throne to him. And with a room full of his supporters all claiming that they had clearly heard the same, whilst staring meaningfully at those who might disagree, with their hands on their sword hilts, who was going to challenge Harold?

Then there was William. King Edward had spent most of his life since 1016 in exile in Normandy; his mother, Emma, was a part of the ruling dynasty. He would have known the younger Duke well. During his time on the throne, Edward was known for bringing Normans into his court, whether as bishops or earls (such as Ralph the Timid who accompanied his uncle, Edward, to England in 1041, and would later become Earl of Hereford).

William was to claim that, at some point in 1051, Edward had offered him the crown. It’s hard to say whether this is true or simply a bare-faced lie on the part of the Duke, seeing the chance to take advantage of a childless king’s death. It is perhaps worth noting, however, that in 1051, King Edward had fallen out with the Godwine family. He had placed his wife, Edith (Harold’s sister) in a convent, while her father had been forced into exile. Though they were later reconciled, the King and Queen never had any children. Whilst it is possible that biology held the answer, there are those that suggest that Edward deliberately avoided this kingly duty so that a grandchild of Earl Godwine might never take the throne.

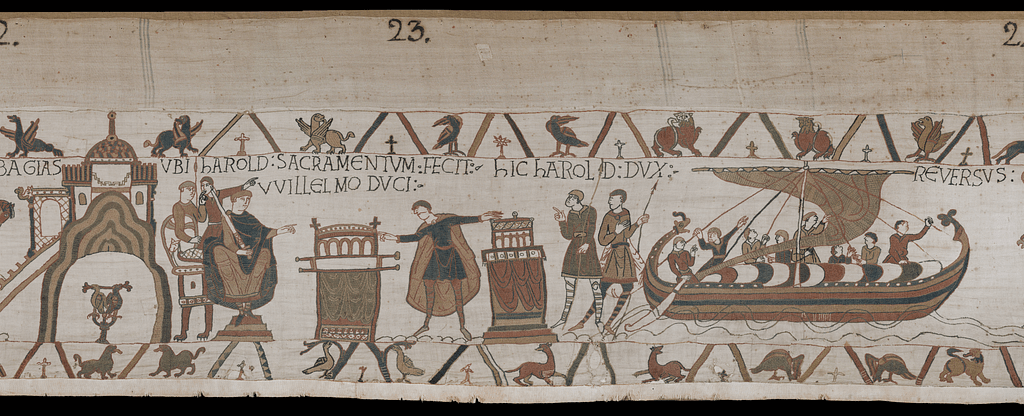

And then, of course, there is the 1064 incident when Harold was shipwrecked on the coast of northern France and ended up in William’s court swearing to support the Duke’s claim. Again, not all the details are clear (including why Harold had gone there in the first place), but I do get the impression that the Earl of Wessex had been seriously outmanoeuvred by the canny Norman.

So far, so clear(ish). However, there was a third candidate whose story carries far less profile than the main protagonists: Edgar Aetheling.

In 1066, Edgar would have been a boy of about thirteen (his birth date is not known). He was the grandson of King Edmund Ironside (Edward’s half brother) who had died in 1016 after a series of battles against the invading Knut of Denmark. Unwilling to do the deed himself, perhaps, Knut had sent Edmund’s young sons to Sweden to be “done away with”, but was thwarted in that desire as the King there refused to kill the boys. Eventually they ended up in Hungary, where the eldest – known as Edward the Exile – married a princess with whom he produced three children; Edgar being the eldest son.

So what? I hear you say… Well, in the mid 1050s, King Edward invested much time in diplomatic efforts to entice Edward the Exile back to England. For what purpose other than to secure a succession plan knowing – as he did by then – that he would have no children of his own.

In the event, Edward the Exile was dead within weeks of returning to England (how and why are not clear, but perhaps someone did not want another player in the mix when the time came. Nevertheless, it would follow logically that Edward the Confessor’s gaze would move from father to son. In conclusion, Edgar’s claim was undone by a combination of his youth and lack of support. Facing the much older, much more powerful and wealthy Harold, it was – perhaps – inevitable that the boy would be eclipsed by Godwineson’s ambition. Had Edward lived for a few more years, until Edgar had reached adulthood, one wonders if the outcome might have been different.

Leave a comment