A Brief History of Falconry in England

I have long toyed with the idea of writing a short blog on falconry (and specifically how & when it came to be popular in England), but never quite got round to it. The idea originated with my novel Blood Price (a standalone murder mystery set in the England of King Knut in the 1020s). The story centred around Sihtric, a retired warrior of renown whose role as Earl Bjarke’s Master of Arms required him to teach the earl’s son all that he needed to know about being a noble lord.

One such skill was the ability to hunt wild animals in their natural habitat with trained birds (the literal definition of falconry). So it was that I included a chapter early on in which Sihtric and Eric spent the afternoon – once the boy’s chores were done of course – flying the earl’s hawks in the countryside. To be honest, the caring for and flying of the birds was largely incidental to the plot; it was more about its use as a vehicle to develop the relationship between the two characters as being central to the advancement of the plot.

Anyway, to make sure I was not being anachronistic, I spent a fair bit of time researching the practice of falconry in pre-Conquest England. You can imagine how disappointed I was then to receive a one-star review which included the following criticism “Poorly researched. Falconry chapter?”

Now, I have no problem with someone not liking one of my books (we all like different things after all), but the assertion that falconry did not belong in a novel set in Anglo-Saxon England struck a nerve, I don’t mind telling you. Still… I’m over it now, though. No, really, I am. Oh alright, I’m lying!

The origins of hunting with birds are unclear, with claims emanating from both China and Mesopotamia. Either way, however, it is reasonable to suggest that we’re talking more than 4,000 years ago (although the first documented evidence takes us back only as far as 722-705 BCE).

From there, the practice of falconry spread slowly west (and east in fact) in line with migrating tribes, improved trade links or, simply, conquest and absorption. For example, it is said that the Goths learned falconry from the Sarmations somewhere between the second and fourth centuries CE, whereas the son of Roman Emperor, Avitus, introduced the practice to Rome in the late 5th century.

As far as England is concerned, though, there are several references in written sources that make it clear that falconry was a sport that was favoured and pursued by the elite sections of society.

The earliest documented reference to falconry dates to c.750 CE when King Aethelberht II of Kent wrote to Boniface (an English missionary working in Germany) asking him to send two falcons (probably gyrfalcons) with ‘skill and courage enough’ to bring down cranes. Given that there were peregrines and goshawks aplenty in England, the king appears to be seeking birds that were not native to the UK.

Later than century, King Offa of Merica was granting charters wherein the privileges included ‘freedom from having to put up the king’s horses, hounds, hawks or the men looking after them’.

Asser’s life of Alfred (Vita Aelfred), written around 893 CE, portrays the king as a very able hunter, while his grandson, Aethelstan, was paid a tribute by rulers in N. Wales which included ‘birds that were trained to make a prey of other birds in the air’.

Then there is the Battle of Maldon poem (written about Earl Byrthnoth’s (in)famous clash in Essex with a Viking army in 991 CE) in which a warrior (possibly Byrthnoth himself) ‘let from his hand fly his beloved hawk away to the woods, and then to battle he stepped.’.

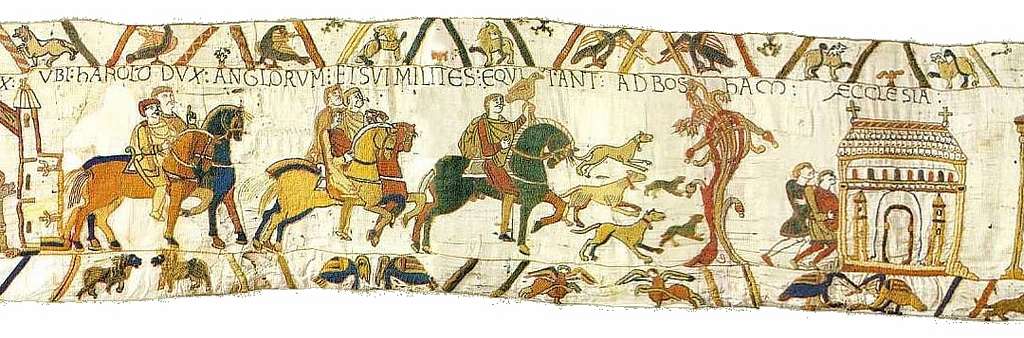

Finally, the most obvious visual reference occurs in the first few sections of the Bayeux Tapestry which depicts King Harold Godwineson out hunting with hawks.

So, without labouring the point too much (irony noted), it is clear that falconry was well established in Anglo-Saxon England and had been for some three hundred years or more by the time of King Knut. It was not some new-fangled foreign fancy brought to these shores by the Normans, but rather a shared interest if you will.

What the Normans did do, however – in that elitest way of theirs – was to place restrictions on who could own or hunt with what kind of birds. The upper classes retained falconry as a sport, suitable only for people of their status, for which they were allowed to use the more noble, long-winged falcons such as gyrfalcons, peregrins and merlins. The lower classes, yeomen and the like, were banned from keeping such fine raptors (and could even be hanged if found doing so). For them, the short-winged birds like the goshawks and sparrowhawks would have to suffice. In their case, falconry was less a sport and more a means of putting food on the table.

Plus ca change, comme on dit en francais.

(NB. all images are public domain / licence free).

Leave a comment