As it has been half-term in the UK this week, the good-lady-teacher-her-indoors and I decided to have a night away, choosing Snowdonia as our destination (Note: not with any intention of climbing mountains!).

Left in charge of route planning (not always a good idea), I took the opportunity to indulge my love of historical locations which Mrs B generally accepts with anything from tolerance to enjoyment (mostly the latter though, I am sure!).

Our first stop was the Pillar of Eliseg. I’d heard mention of it a few times and had read a couple of articles about it, but had never actually seen it. You can imagine my surprise when I found it was pretty much (honest) on our route from Cheshire to Betws-y-Coed.

What and where is the Pillar of Eliseg?

Good question; I’m glad you asked.

It’s a stone pillar made from locally sourced Gwespyr sandstone. What you can see today is all that remains of what was originally a much taller (possibly up to 4m in height) cross that dates back to the first half of the 9th century. The bronze age burial mound on which it stands is much older (roughly c.4,000 years in fact).

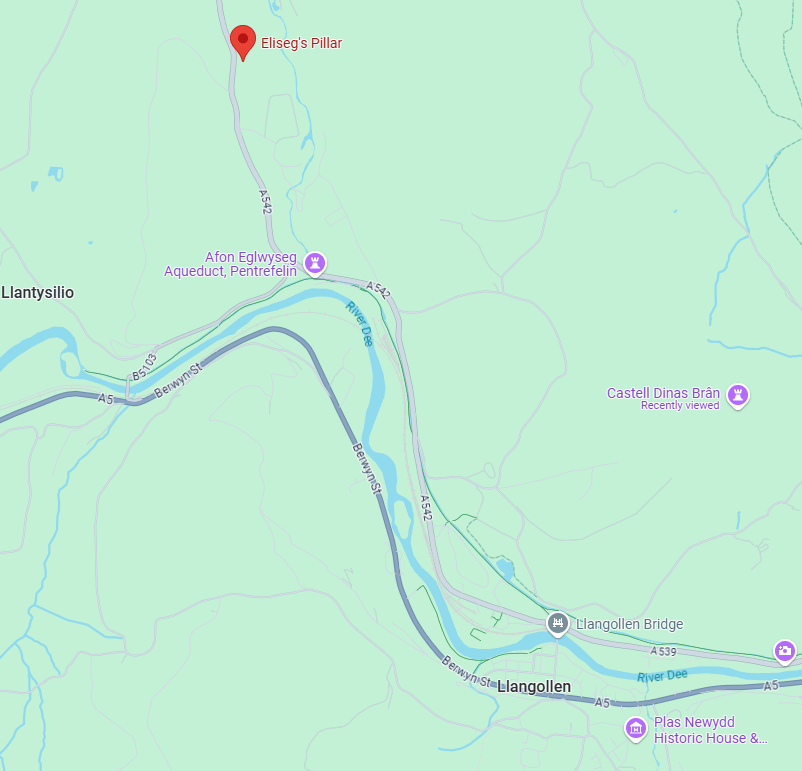

You’ll find the pillar about 2 miles north of Llangollen in the county of Denbighshire (just east of the A542 for those, like my dad, who value a road reference). It is situated in farmland about 50m to the right of the road as you go north. Blink and you’ll miss it. (Author’s note: I did miss it, but my trusty co-pilot had my back).

What is so remarkable about the Pillar?

Although the bronze age burial mound is of great interest (containing burials of several bodies, possibly of a family group over a period of time), and the pillar itself is a rare example of still standing monuments from this era, it is the – now lost – Latin inscription on the west face that marks Eliseg’s Pillar out as special.

Although totally unreadable now, various transcriptions were made by antiquarians over the years, the best of which, by Edward Lhuyd in 1696, reproduced 31 lines of the original inscription. Unfortunately, this does not represent the complete wording as, even by his time, some of the text was already illegible. The lines that we do have, however, provide a fascinating insight into the history of this region and beyond from the time of its erection right back to the days of the end of the Roman era in Britain.

Translation of Latin inscription

(i.e. the 31 lines transcribed by Edward Lhuyd)

+Concenn son of Cattell, Cattell son of Brochmail, Brochmail son of Eliseg, Eliseg son of Guoillauc.

+Concenn therefore, great-grandson of Eliseg, erected this stone for his great-grandfather Eliseg.

+It was Eliseg who united the inheritance of Powys … however through force … from the power of the English … land with his sword by fire(?).

[+] Whosoever shall read out loud this hand-inscribed … let him give a blessing [on the soul of] Eliseg.

+It is Concenn … with his hand …his own kingdom of Powys … and which … the mountain.

… monarchy … Maximus of Britain … Pascent … Maun Annan … Britu moreover [was] the son of Guarthigirn whom Germanus blessed [and whom] Sevira bore to him, the daughter of Maximus the king, who killed the king of the Romans.

+Conmarch represented pictorially this writing at the demand of his king, Concenn.

+The blessing of the Lord upon Concenn and likewise on all of his household and upon the province of Powys until …

So, what can we glean from the text?

First, and most obviously, we can say that it was King Concenn, son of Cattell (also expressed as Cyngen ap Cadell), who ordered the pillar to be erected. This helps date the monument to the first half of the 9th century, as Concenn is known from other sources to have lived from 808 to 854/55.

Second, we know he dedicated the cross to his great-grandfather, Eliseg (Elisedd) ap Guoillauc (Gwylog), who is thought to have been a contemporary of the Mercian King Offa (of whom most people will have heard… the Dyke? On the border between Wales and England? Yes, that one).

The inscription, incomplete as it is, appears to celebrate the fact that Concenn’s forebear had managed to evict the English from his lands and thereby establish, or consolidate, his realm of Powys. Given Offa’s powerful overlordship of much of England at the time, this represents a significant achievement, if true, and could – perhaps – provide an alternative motivation for why the Dyke was built. Not so much a statement of Offa’s power, more a desire to shut the Welsh up (literally and figuratively). It’s a stretch, I’ll admit, but not wholly implausible.

With that kind of Powys prowess (sorry!) on display, it is not surprising that Concenn would want to celebrate that history and, perhaps more importantly, lay a claim to be its rightful descendant. By associating himself with that glorious past, he is drawing attention to the legitimacy of his rule, underlining his own credentials. Why he felt the need to do this, however, is unclear but not beyond the bounds of speculation.

The text also provides us with much interesting and significant detail in respect of the genealogical history of Powys. For example, some familiar names will leap out at those who know a thing or two about late Roman / early medieval Britain.

The Maximus of Britain refers to Magnus Maximus who was an officer in the Roman army serving in Britannia in the late 4th century. In 383, he was proclaimed emperor after which he invaded Gaul (taking most of the Britannia-based legions with him). There, he defeated and ultimately killed the existing emperor, Gratian (hence: “who killed the King of the Romans”).

The pillar also adds that a daughter of Maximus (Sevira – not known from any other sources), was married to Guarthigirn (more commonly represented as Vortigern – he who supposedly invited the Saxons to Britain as foederati, or mercenaries and… well, the rest is history). It goes on to state that Vortigern had been blessed by Bishop Germanus whom we know from Bede had visited Britain c.429 to deal with the Pelagian heresy.

Note: Another, more recent, source for the bishop’s visit can be found in the King Arthur film, starring Clive Owen (2004).

Additional Note: this is not to be confused with the ‘cor blimey, geezer’, version by Guy Ritchie, starring David Beckham (2017). I kid you not. I watched that monstrosity for the sake of research – albeit through my fingers!).

One final thing worthy of note is the fact that the Latin text suggests that the inscription was intended to be spoken out loud (the use of the Latin word ‘recitare’ – i.e. recite).

‘Whosoever shall read out loud this hand-inscribed … let him give a blessing [on the soul of] Eliseg.’

If that is the case, then it may provide a tantalizing glimpse into the political and / or militaristic practices of the time. Did the pillar serve as an important mustering point for the Powysian army? Was it a meeting place where embassies might be received or treaties concluded? Did Eliseg meet there with Offa? Were Kings of Powys acclaimed there?

Its location certainly suggests that a degree of importance could be assumed, in that the valley in which it is sited is the confluence of a number of ancient trackways.

One last thing of note…

That the pillar still carried great resonance in the region, even up to the 13th century, is apparent from the fact that the nearby Valle Crucis abbey whose name – as students of Latin will know – references the pillar (and also hints at the fact that it was originally a cross). The words literally mean: the abbey in the valley of the cross.

So, while there may not be much to see, it is worth ten minutes of your time if passing, just to stand there and cast yourself back to the age in which Kings of Powys might have mustered their army by the pillar, ready to do battle with their troublesome Aenglisc neighbours.

Leave a comment