Those of you who keep an eye on such things may have seen Donald Trump announce on 20th May 2025 that an architecture had been selected for his Golden Dome project and that the system would be operational before the end of his term at a cost of c. $175bn. With much the same intent as Ronald Reagan’s derided Strategic Defense Initiative (or Star Wars) programme back in the 80s, its aim is to provide the USA with a next-generation defence system that will protect the country from possible missile strikes.

So what, I hear you ask, can this possibly have to do with the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia in the late 9th and early 10th centuries? Well, as President Harry S Truman once said, “There is nothing new in the world except the history you do not know.”

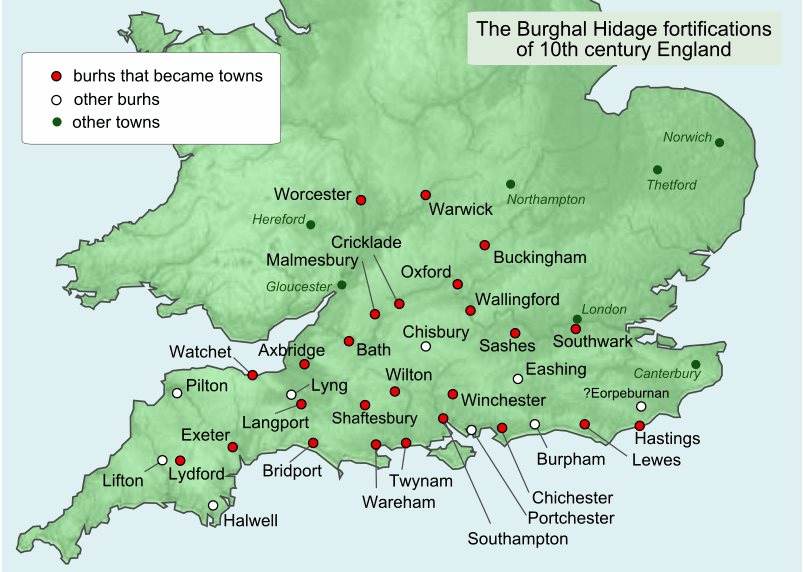

With that in mind, allow me to bring to light some of that history which shows how King Alfred the Great had long ago come up with the same idea and – unlike any current or former US president so far – reaped the intended benefits of its successful implementation. In so doing, Alfred and his progeny were able to, initially, protect Wessex from the threat of Viking invasion and, thereafter, lay the foundations for the concept we now know as England. Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you the Anglo-Saxon Burh.

The Anglo-Saxon what, now?

Burh. From which we derive the word borough today (and also seen in place names ending in -bury or -burgh). The word burh or burg is an old English development of an earlier Germanic term which, in its verb sense (berg-an) meant to shut in for protection. As such, we can best interpret the word as ‘fort’ or fortress’.

Where did the idea come from?

Since the start of the Viking raids in the late 8th century, but more especially since the arrival of the Great Heathen Army in the 860s, England’s four main kingdoms (Northumbria, East Anglia, Mercia and Wessex) had been subject to periodic and often devastating raids from Norse adventurers. Often, it was a case of smash and grab raids on coastal towns or churches wherein the Vikings would take what valuables (including people to sell as slaves) they could and kill anyone who tried to stop them, before escaping on their boats ahead of the arrival of the local lord or king.

Things changed in the 860s, however, in that the army that arrived clearly intended to stay, to stake a claim to vast swathes of England. Northumbria and East Anglia were quickly overrun, while Mercia’s king had to flee, leaving a puppet ruler controlled by the Danes. In fact, by the mid-870s, only Wessex really remained as a wholly independent ‘English’ kingdom, ruled by our good friend, Alfred. And even Wessex was under massive pressure, most notably in January 878 when the Vikings launched a surprise attack on the royal vill at Chippenham. Forced to flee into the Aethelney marshes, with only his closest retainers, Alfred set about building a new defensive strategy to deal with the foreign invader, the cornerstone of which would be a network of fortified burhs across the whole kingdom.

So, what was a burh?

In short, it was a fortified town. Fortified in the sense of earthworks, wooden palisades, or stone walls (or some combination thereof). As you may know, this era predates the concept of the castle (adopted from the Normans in the mid 11th century); as such, Anglo-Saxon England found itself vulnerable to Viking raids in which they had little option other than to meet the enemy in open battle… which did not always go well. This was often after one or more towns had been sacked and their people slaughtered.

Learning from this, Alfred realised two things. Firstly, that the towns in Wessex needed protection, and the people needed a place of refuge to shelter from attack. Without some sort of fortification, they would forever be largely defenceless against raiders. Secondly, that if he had a network of such burhs across the country, then they could form an effective defensive shield against an enemy.

With each one planned so that no one would ever be more than twenty miles (or a day’s march) from a burh, any town that found itself under attack could hope to hold out until the arrival of reinforcements from the next town (or towns), at which point the Vikings would be caught between the relieving army and the besieged burh’s defenders. On top of this, building an improved network of roads to connect the burhs (known as herepaths: literally, military/army road) helped enable the faster relocation of troops and refugees.

Note: he also ensured that the town’s inhabitants were equipped, trained and organised in such a way that at any moment, half of them would be ‘on duty’ and half not (so that the latter could continue the important business of farming, tanning, metalwork etc.).

What did a burh look like?

Unlike early Saxon settlements (for which the word higgledy-piggledy might have been invented to describe their lay out), the newly created burhs often adopted a grid-like street pattern. Not dissimilar to what the Romans had done in their towns centuries earlier.

Imagining of a typical burh layout (Public domain)

In fact, it is no coincidence that a good proportion of burhs were built on top of existing Roman sites. As well as the existing, structured lay out, there were other benefits to be accrued from this recycling approach:

- Roman sites tended to be located at or near critical communication hubs (e.g. junctions on major road networks). Gloucester and Chester are good examples of this.

- The sites often had existing fortifications, which just needed to be repaired or improved.

- Roman sites had often become centres of Christian influence, a phenomenon much more prevalent in the south, in contrast to Celtic Christianity in the north that prioritised evangelisation in the countryside.

There are, of course, many examples of burhs that were established in entirely new places. Wallingford, Wareham and Wilton, to name but three, serve as examples here, using earthen ramparts topped with wooden palisades for their protection. In other cases, sites with natural defences could be chosen – e.g. on promontories where a single ditch and bank might be all that was needed to block the one accessible approach. Lewes, Lydford and Lyng fall into this category.

It should also come as no surprise that, once established, burhs often became centres of commerce and local government, from which the concept of what we would recognise as a town, would slowly emerge.

How successful were they?

In a word: very. And on more than one level, too. Militarily, they stabilised Wessex, providing a far more dynamic and effective system of defence against the Vikings than before. From 878 onwards, the West Saxons were able to resist more robustly before then starting to push the enemy back until, by the time of Alfred’s death, Wessex’s borders were secure. Progress was also being made in prising Mercia from under Danish influence.

The fact that Alfred’s children, Edward the Elder and Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, continued the strategy across much of Mercia after their father’s death is further proof of its success. Together, they laid the foundations for Edward’s son – Aethelstan – to achieve something that had not been seen before: a unified English-speaking nation.

But the burhs achieved much more than that. The structured planning combined with local, community effort to build and maintain each burh is evidence of a new and more rigorous approach in terms of centralised government underpinned by local enforcement. This in turn helped encourage commercial and social developments which ultimately gave rise to what we now recognise as towns.

I’m also sure it came at a fraction of the cost, too.

Leave a comment