Over the years, the market town of Ludlow has become a regular haunt for me and the good lady teacher, her-indoors. Not only is it a lovely town with many fine historical buildings (500 listed buildings in total, if you were curious), but it possesses what – for me – is one of (if not, the) finest castles in England (I’ll grant you some of the Welsh castles rival it!). Oh, and it has several fine pubs too. What more could a history nerd want?

Example of one the many half-timbered buildings in Ludlow (Author’s own photo)

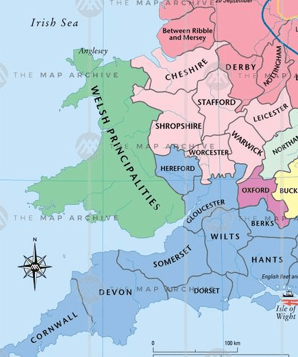

The town lies in Shropshire, close to the border with Wales, and almost equi-distant between Shrewsbury and Hereford. Its name derives from the Old English: Hludhlaeh (roughly translates to ‘the hill by the loud waters’).

Note: at that time, the River Teme was rather more boisterous than it is today, hence the noise made by the rapids would have been clearly audible up on the promontory on which the town (and castle) were built.

According to its website, the castle had its origins in the 1070s. Shortly after the Norman Conquest, the region of England that bordered Wales soon became a focus of unrest that required strong, committed leaders to keep the peace (or enforce Norman rule as it might also be described).

To that end, King William created earldoms along the border and gave them to his most trusted and competent followers, one of whom was William FitzOsbern (who’d accompanied the king to England in 1066). FitzOsbern was granted the Earldom of Hereford and he, in turn, granted the manor of Stanton (amongst others) to one of his followers – Walter de Lacy. Walter chose this manor to be the site of one of what would become a string of castles whose purpose was to secure the border.

Inside the bailey, looking to the keep and main gate (author’s own photo)

Note: One of the key leaders of resistance to Norman rule in Shropshire was Eadric the Wild. You can learn more about his strife with FitzOsbern and the Normans in the third book of my Huscarl Chronicles trilogy: Thurkill’s Rebellion.

Early history of Ludlow Castle

It is possible that the first iteration of the castle (then known as Dinham Castle) was constructed of wood. However, this would be quickly upgraded to stone from 1085 by Walter’s eldest son, Roger.

The early history of Ludlow castle was tumultuous to say the least. Strap in and bear with me; the Normans were spectacularly unoriginal when it came to choosing names for their children. An especially annoying trait was for a son to be named for the father (William II Rufus as the second son of William the Conqueror being a prime example). It is easy to become confused.

Roger de Lacey did not live to see the completion of Ludlow castle, and nor was he to play a part in its construction after 1095. He forfeited that right when, in that year, he rebelled against King William Rufus (for a second time). Rather than being executed, however, he was stripped of his lands (which were given to his brother, Hugh) and exiled.

When Hugh died, childless, in 1115, the ownership of the castle fell into dispute. The new king (and Rufus’ younger brother) – Henry I – gave the castle to Hugh’s (probable) niece, Sybil, whom he then married to one of his household staff, Pain FitzJohn.

Note: to be fair, I have never come across another Norman called Pain, so respect to his dad, John, for picking such a unique name. That said, calling him Bread is odd. Perhaps it should be seen as the medieval equivalent of Chardonnay today (with apologies to any readers so-named!). I very much doubt that Pain’s mother played any part in that decision)

When Pain died in 1137, the castle became one of many pawns between King Stephen and Henry I’s daughter, Mathilda, during what became known as the Anarchy (the period that followed King Henry I’s death (in 1135) without legitimate male heir).

Sidenote: Henry I remains the current holder of the record (of any monarch of England) for fathering the most illegitimate children (23, give or take). It is something of an irony then that he only managed a single legitimate son (William – again!), who died in the White Ship disaster of 1120. Henry’s inability to sufficiently impregnate the correct woman led to a civil war that was, arguably, more devastating than its 17th Century counterpart.

Wreck of the White Ship by Joseph Martin Kronheim (1810–96) – Public domain.

Having seized the throne, Stephen needed to secure his position. He therefore gave the castle to Robert FitzMiles (who’d been planning to marry Pain’s daughter) in return for his political support. This was, understandably, to the annoyance of Roger de Lacey’s son, Gilbert, who’d also – quite reasonably – laid claim to it.

To cut a long story short, even though Stephen successfully captured the castle in 1139, Gilbert refused to accept defeat. Instead, he began what was, in effect, a private war against the castellan, Joce de Dinan (husband of Sybil), ultimately taking it in the early 1150s. Thereafter, the castle remained under the ownership of the de Lacey family until the end of the next century.

What might have been . . .

To cover every aspect of the history of Ludlow castle would be a feat beyond the bounds of this blog (and probably beyond the storage limit on my website too). That said, I would like to end with another extraordinarily interesting ‘what-if’ scenario involving the castle in the early 16th century.

Once Henry VII came to the throne in 1485 (after the battle of Bosworth), he continued to use Ludlow as a

stronghold in the region, before granting the castle to his eldest son, Prince Arthur, in 1493. Ludlow was to be the location for Arthur’s honeymoon in 1501 when he arrived there with his new bride, Catherine of Aragon (yes, that one). Though why the couple didn’t just jet off to the Costa Dorada (part of medieval kingdom of Aragon) for some sun, sea, sand and… sangria is anybody’s guess. Ludlow must have been quite the attraction then, as now.

Within a year, however, Prince Arthur was dead (let’s not blame the food or climate). The couple were said to have been afflicted by “a malign vapour which proceeded from the air”, often interpreted as the mystical Sweating Sickness. While Catherine recovered, Arthur was to die on 2nd April 1502, at the age of just 15. His body was buried in Worcester Cathedral, though his heart was interred in Ludlow in the nearby church of St Laurence where a plaque marks the supposed spot.

Not only did the young prince’s death deprive us of a genuine King Arthur, it was also to usher in one of the most significant upheavals in English history: the dissolution of the monasteries. At the time of Arthur’s death, Catherine of Aragon swore that the marriage had never been consummated. Still keen to secure an alliance with the Spanish kingdom, this left the door open for Henry VII to offer his second son (the later Henry VIII) as her new husband.

By 1529, the couple’s inability to produce a male heir would lead to our separation from the Church of Rome, the creation of the Church of England with the king at its head (via the Act of Supremacy in 1534) and the forced acquisition of the assets of the Catholic Church in England and Wales (in this author’s opinion – admittedly from a considerable distance – probably the worst act of iconoclasm in our history).

The trigger for all of this was Henry’s desire to divorce Catherine (he called into question his wife’s claim of virginity, thereby establishing that it had been wrong for him to marry his brother’s wife). All this to enable him to marry Anne Boleyn in his incessant pursuit of fathering a male heir.

Leave a comment