A Pot Pourri of delectable detail

Note: all images used in this blog are public domain

It’s not been seen on these shores for more than 900 years, not since its creation to document the events leading up to and including the Norman invasion of England in 1066. But now, the Bayeux Tapestry (hereafter: BT) is on its way from France to England (to the British Museum to be precise), as part of a swap deal brokered between the two countries.

To mark the run up to this historic occasion (it will be displayed for the best part of a year from Autumn 2026), I present for you a smorgasbord of interesting facts and fables about this most incredible and important artistic masterpiece.

- Let’s get this one out of the way: pedantically speaking (Who? Me?) it’s an embroidery and not a tapestry. The latter are woven on a loom, whereas the BT was made by hand, with strands of coloured wool stitched onto a piece of linen.

- It is widely believed (though not conclusively so) to have been made in England – possibly by nuns in Canterbury. The evidence for this derives from the fact that the Latin text, artistry and needlework are very similar to other, equivalent works of that era.

3. Also not definitive, but the BT was most likely commissioned to celebrate the Norman victory by Odo, Bishop of Bayeux – the Conqueror’s half-brother who accompanied him in 1066. Certainly, Odo features prominently throughout the BT and never in a bad light. I guess its modern-day equivalent might be a set of commemorative Battle of Britain ceramic plates; the kind of thing you see advertised in the Mail on Sunday Magazine.

4. It’s not complete. Even though it’s 70 metres long, there’s a bit missing off the end (a supposition put forward due to the frayed edges which might suggest a ‘deleted’ scene). Currently, the BT ends with the Saxons fleeing from the Battle of Hastings following the death of King Harold, but historians think that the final scene would have depicted William’s coronation in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day in 1066. That would certainly make more sense as a concluding ‘up yours’ to the English, as it were.

We can only wonder if that missing bit of fabric will ever show up, or (possibly) whether it was never finished.

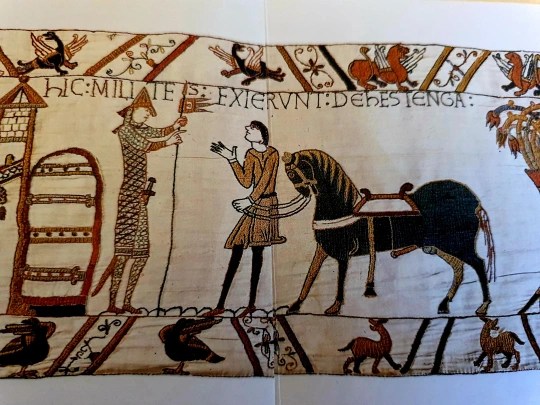

5. The Latin is a bit shit. It brings to mind the famous Latin lesson in Monty Python’s Life of Brian (“People called ‘Romanes’ they go the house”), or perhaps the Friends episode where Joey Tribbiani states on his acting résumé that he can ride a horse. Either way, the captions that accompany the various scenes are not always textbook Latin: grammatical errors, spelling variations and strange abbreviations abound. Were they in a rush? Did they go for the cheapest quote (caveat emptor … I thank you!)? Or were mistakes made from listening to a verbal dictation? Either way, the need for proof readers and editors was as strong then as it is now.

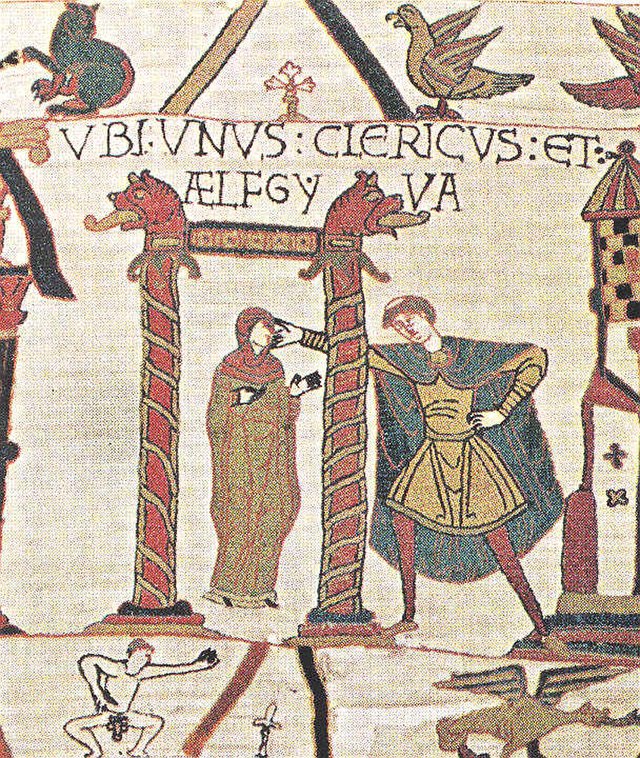

6. Similar to a block-buster Hollywood war film, the BT features very few women – a total of three to be precise. Of these three, only one is named: Aelfgyva. A huge amount of ink (and bytes, I suppose) has been expended on her over the years, but we are not much closer to knowing who she was or what role she played in the events of that year. Note the sexually charged imagery in the surrounding scene (see #7 below re. willies!)

7. Which brings us to willies (I apologise in advance!). This has been the subject of some scholarly debate in recent months (No, really. I’m not dicking about here).

Professor George Garnett of Oxford University counted 93 penises back in 2018 (of which 88 belong to horses, apparently). Quite why he did that is unclear… But then in a move that rocked the historical world to its very foundations, Dr Christopher Monk claimed there was a 6th human nob. Back then comes Garnett to poo-poo that theory saying this new example cannot be a penis because it has a yellow blob on the end (and was therefore more likely to be a scabbard).

In what was perhaps a reassuring note regarding 11th century genital hygiene, Garnett added (as proof) that none of the five incontrovertibly human cocks had yellow blobs on the end.

People get paid for this stuff. I’m in the wrong game.

Quite what the penises are doing on the tapestry (no sniggering at the back, Frobisher), is anyone’s guess. My guess is one of the nun’s younger brothers snuck in overnight and added them for a dare.

As a final, illuminating note on the subject (I really am milking it, aren’t I?): when the ladies of the Leek Embroidery Society made a copy of the BT in the 19th century (now on display in Reading Museum), they added underpants in most cases (presumably not on the horses). Must have been considered a bit racy for Victorian Staffordshire.

Oh go on, you twisted my arm… the largest of the 93 penises on the BT belongs to… you guessed it: Duke William’s horse. The 11th century equivalent of a ‘small’ man driving an expensive sports car, perhaps.

I’ve finished with the penises now – I promise.

8. The BT shows that propaganda and fake news is nothing new in the world. One of its key aims (underlying the fact that it must have been commissioned by a Norman – likely, Odo) is to present William as the righter of wrongs: specifically in terms of the supposed ‘oath-breaking’ usurper Harold Godwineson (whom the Normans never recognised as having been King of England). They take care to show Harold swearing an oath on holy relics (that time when he pitched up in Normandy c.1064), enabling the invasion to be portrayed as divine retribution.

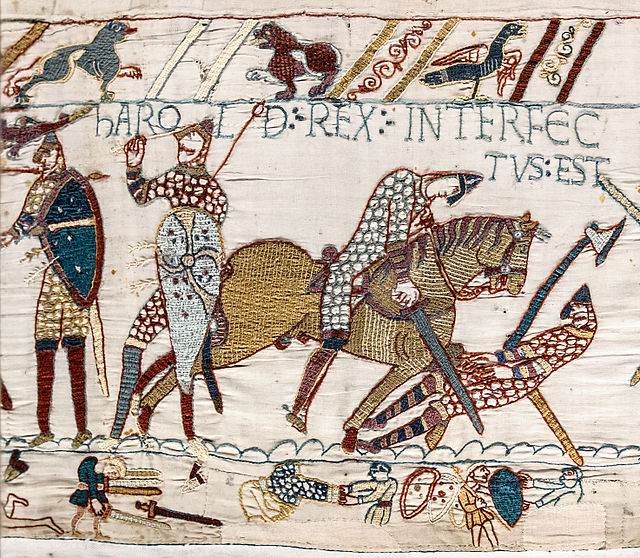

9. One of the most controversial aspects of the BT is the scene supposedly depicting the death of King Harold (the famous ‘Hic Harold Rex interfectus est’ tableau).

I have already written an article on this subject, which I won’t rehearse here, but suffice to say, the depiction of a man with an arrow in his eye is problematic for two significant reasons:

a) It may not be Harold; the man in the next image is shown being cut down with a sword. This second man carries a battle axe and no shield, whereas the first man has a shield and no axe.

b) There is substantial evidence that shows that the supposed arrow was the result of an alteration made in more recent times when undertaking restoration work. The original scene more likely has this first man holding a spear (as is the case in many other images on the BT).

10. The more recent history of the BT has not been without its thrills and spills. During the French Revolution, it was confiscated by the new government and put to work as a covering for military wagons. Sacre Bleu. Mon Dieu. Quite!

Then, three days before the Wehrmacht were due to evacuate Paris in August 1944, Heinrich Himmler sent a coded message ordering the BT to be moved to Berlin. The message was intercepted at Bletchley Park, enabling the French to secure the Louvre (where it was housed at the time) before that could happen. Another win for Alan Turing right there!

In conclusion, if you have the chance, you should definitely make time to visit the Bayeux Tapestry when it comes to London. I was fortunate enough to see it in Bayeux 20+ years ago; it is far more impressive in real life is all I will say.

Leave a comment