Today’s blog takes us back to January 1069, to a day when the streets of Durham ran red with Norman blood, giving birth to an uprising that properly gave King William I the willies.

Founded in 995 by a group of monks from Lindisfarne when they chose the high ground enclosed by a loop of the River Wear to be the new home for the body of Saint Cuthbert. Prior to that, it had been at Chester-Le-Street, after the monks had first fled from the Viking attacks on Lindisfarne back in the late 8th century.

Side note: Cuthbert’s shrine can still be seen in Durham Cathedral, along with the gifts presented by King Aethelstan when he prayed at the shrine in Chester-Le-Street on his way to fight the Scots in 934. Well worth a visit.

So, how did Durham come to be the setting of one of the worst documented massacres ever to take place on English soil?

The most important ingredient was, of course, the Norman invaders. But what was it specifically that had the northerners (and several other parts of the country, for that matter) all riled up?

For the most part, it came down to land. In the years after 1066, all manner of means (fair or foul – but mostly foul) were used to effect a wholesale transfer of land ownership from Saxon to Norman.

- Confiscation – those who had fought and/or died for Harold were declared traitors (on the basis that the Normans saw Godwineson as a usurper). In a single stroke, sons were dispossessed, robbing them of centuries of hereditary rights

- Forced marriage – English widows were forced to marry Normans so that the latter would acquire the rights to their inheritance. As you might imagine, few of these liaisons would have been founded on love, let alone respect. A brutal existence for many of those women

- Transfer fees – in those cases where sons could succeed fathers, King William would set massive ‘inheritance taxes’ in terms of a levy the son would have to pay to ratify their title to the land. Makes the recent farmers’ protests look like a disagreement over whose right of way it is on a roundabout.

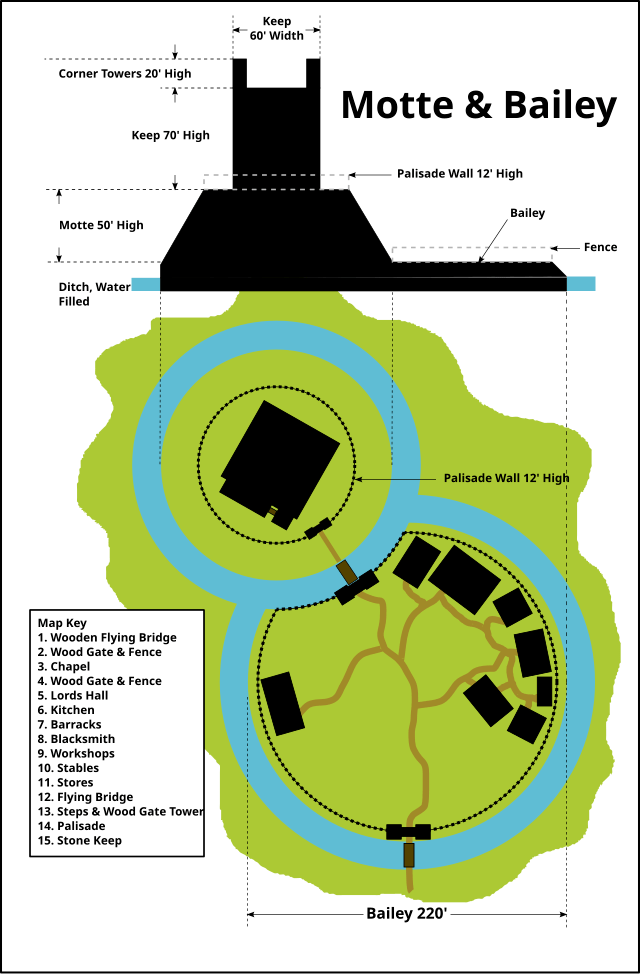

Then there were these new-fangled things called castles springing up all over England every five minutes / five miles. Actually, the first castle on English soil was probably built in the 1050s (in the border region with Wales) by one of Edward the Confessor’s Norman cronies. But from 1066, they proliferated to say the least. A tried and trusted method of pacifying a region in Normandy, it was perhaps inevitable that they would also be exported to England.

For the Saxons, though, it was their blood, sweat and tears that went into building the things and it was their lives that were subsequently dominated by the structures.

Thirdly (and finally for this abridged list), the north of England had a long and turbulent history since its heyday in the 7th century. More than most parts of England, arguments tended to be settled with a sword while grievances became feuds that could last for centuries. They were not known for taking kindly to uninvited outside interference.

For the most part, the West Saxon Kings of England left the north to look after itself; imposing Harold’s brother, Tostig, as their earl in 1055 was the exception that proves the rule. That experiment ended in 1065 with Tostig being forced into exile (by his own brother) after the locals had set about his tax collectors, having run out of patience with their greed and corruption.

King William’s accession marked a significant change in approach, though, as the Norman was determined to stamp his authority over the whole of his dominion. Outside interference was going to be the new norm.

January 31st 1069

So, how did the massacre come about?

Back in 1067, King William had appointed a Yorkshire thegn, Copsig, to be Earl of the northern half of Northumbria. This was a gob-smacking move when you consider that Copsig had been Tostig’s right hand thug before the conquest and was Mr. February on the North’s ‘top 10 most-hated men’ calendar for that year (Tostig appearing as Mr. January, of course. Despite being dead).

What was William thinking? Perhaps he was seduced by Copsig’s honeyed words (“Stand on me, Guv, I’ve got this”). Perhaps he thought it would only be a temporary measure, until he could give the area his undivided attention? Or perhaps he just really needed the cash that Copsig was willing to pay. It was a few months after Hastings and there were many soldiers still to be paid.

Either way, hindsight suggests that it was never going to end well. Within a few weeks of his arrival, Copsig was ambushed and killed by the ‘existing’ Earl Oswulf (who had not submitted to William), only for him to then be killed by “a robber” a few months later. You start to see the pattern for these parts.

The next man to arrive on the scene was Gospatric, a kinsman of Earl Oswulf and therefore a scion of the ruling house of Northumbria. Grabbing hold of his balls for courage, he went to petition William for the earldom (i.e. that part that lay north of the Tyne). It was a ballsy move, for sure, given that Oswulf had only recently murdered the king’s previous choice of incumbent. Nevertheless, it clearly worked as William granted Gospatric the title upon payment (naturally) of a large bundle of used, unmarked notes. Clearly pragmatism and a continual need for hard cash were still driving the agenda.

Things were calm for a bit until, in 1068, the growing resentment of William’s land redistribution policy (see above) finally erupted into all out rebellion in the north. All the big names were there: Earls Eadwine and Morcar (of Mercia and Northumbria respectively); Maerleswein, the governor of York, Gospatric of Bamburgh (despite only recently having submitted to William); and Aethelwine, the Bishop of Durham (though the elderly churchman may not have been much cop if it came to a scrap).

But above all of those was the one name that really mattered: Edgar Aetheling. He was the last Anglo-Saxon King of England (acclaimed by the Witan in the aftermath of Hastings) who had been forced to submit to William in early December 1066. As a figurehead around whom the English could rally, his involvement made this uprising properly dangerous.

So it was that the king hurried north with a huge army, harrying the land as he came and adding to his collection of castles.

Not for the first (or last) time, Eadwine and Morcar got cold feet, scarpering faster than a boy found by a farmer in the hay bales with his daughter. Without their troops, the rebellion soon fizzled out with most of the other names, Gospatric included, fleeing north to Scotland.

Reaching the latter months of 1068, William might be forgiven for thinking (once again) that things were settling down a bit. Risings were being put down and there was evidence that more and more of the English were willing to respect his authority.

If that made for a more pleasant Christmas, the king was brought rapidly back down to earth in January 1069. Eager to put an end to the nonsense in the north, and mindful of the fact that having twice appointed Englishmen to rule the region (one of whom had been killed and the other rebelled), William decided to change tack; he brought in an outsider by the name of Robert Cumin, a spicy sort most probably from Flanders (the town of Comines, specifically).

Perhaps wishing to avoid the fate of his predecessor, Robert travelled north with a considerable force: anywhere between 500 and 900 men. On the way, he appears to have adopted the tried and trusted method of wreaking destruction, no doubt hoping to set the tone for the locals. He was not messing about. Rather than face him, in fact, many of those who lived north of the Tyne tried to flee, but found their efforts hampered by such bad weather which made the hills and dales of the region nigh on impassable.

With no other option left to them, the plucky souls put on their big-boy pants and resolved to stand and fight against this foreign upstart.

With some premonition of the future, perhaps, or – more likely – knowing what hard bastards they were oop north, Bishop Aethelwine of Durham tried to avert disaster by going to see Robert Cumin to dissuade him from coming to the city. But with what we might call typical Norman arrogance, the Fleming ignored the old man. Surely, no one would dare stop him from entering Durham.

Reaching the city, Cumin allowed his soldiers to loot and pillage in their search for billets for the night. If this was a straw, it was the final one; the stage was set for what was to come.

The tale is then taken up by Simeon of Durham (a Benedictine monk in Durham Cathedral who wrote his Historia Regum chronicle in the early 12th century).

He relates how the Northumbrians ‘at dawn burst the gates [of Durham] with great force, and slew on every side, the earl’s [i.e. Cumin’s] men, who were taken by surprise’.

Simeon paints a very vivid picture of the ferocity with which the attack was pursued, saying that Norman soldiers were killed wherever they were found: in the streets and in the houses. Presumably they were stumbling around half-dressed with the mother of all hangovers having consumed copious stolen barrels of beer and wine the previous evening. It’s tempting to imagine Durham’s inhabitants joining in with the slaughter, wreaking revenge for despoiled womenfolk and lost goods.

As for Cumin, well he had been lodging in the bishop’s dwellings with his bodyguard. When the rebels attacked, however, they found themselves beaten back by the earl’s men, unable to ‘withstand the javelins of the defenders’.

Not to be put off, and being resourceful chaps, they set fire to the lodgings (Bishop Aethelwine can’t have been too pleased). We’re told that once the flames became too hot, some men burst out into the open, only to be cut down, while the rest – including Cumin – perished in the inferno.

Simeon then ends by saying that of seven hundred men, none but one escaped, who thereby won gold in the inaugural hide and seek world championships.

It was an incredible victory, a seismic statement. Not since Hastings in 1066 had so many of the hated foreigners been killed in a single day. It sent shockwaves around the country and became the trigger point for yet another uprising in the north, enticing Edgar, Gospatric and Maerleswein back from their Scottish exile.

But whilst English confidence would have soared, quickly stoked by another great victory in York, they must have known there would be repercussions. Perhaps they welcomed it, thinking that they had proved the Normans were not invincible after all. Maybe they thought that the pendulum had swung in their favour at last.

What was to follow, however, brought a new level of horror and brutality to the land, and is often referred to as the Harrying of the North. More of that another time.

Note: the events referred to above form the backbone of my Rebellion trilogy, of which book 3 should be released later in 2025.

Leave a comment