To mark its recent 540th anniversary (I missed it as I was away in Scotland), here are 10 facts, thoughts, opinions and otherwise, general tomfoolery about the battle which you may not otherwise have known (nor realised you needed to).

1. When and where did the battle take place?

The when is easy: 22nd August 1485.

The where is slightly more complex. If, like me, you visited the site 20 plus years ago, you would have gone to the visitor centre located close to Ambion Hill and, perhaps, followed the series of placards around that area reading about how the armies lined up and how the battle unfolded. Turns out that was mostly bollocks. Sorry.

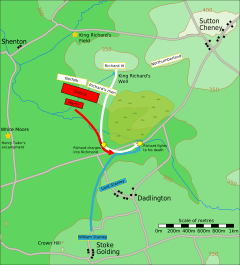

Following some groundbreaking archaeological surveying in 2010, new evidence was uncovered (in short, lots of cannon shot, a silver boar badge probably worn by one of Richard’s closest adherents and likely lost in the final charge and other exciting, battle-related stuff) which has allowed us to pinpoint the location to an area near Fenn Lane farm (straddling a Roman road, itself known as Fenn Lane), some 3km southwest of Ambion Hill.

2. Who were the main protagonists?

Unusually for most medieval battles, there were actually 3 armies in the field on that day:

- King Richard III. An experienced and battle-proven warrior, his army numbered between 8-12,000 men split into 3 divisions (or ‘battles’). The Duke of Norfolk led the vanguard (positioned on the right flank), Richard had the centre, while Henry Percy, the Duke of Northumberland (forebear of Lord Percy Percy of Blackadder fame) had the rearguard, or left flank.

- Henry Tudor. A stranger to England (his 28 years had been split equally between Wales and Brittany (the latter, in exile), and unversed in military matters. His army numbered 5-8,000 and he could, therefore, have been outnumbered 2 to 1. To make up for his lack of experience, the canny Henry recruited veteran, proven generals to lead his forces (notably John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, and his own uncle, Jasper Tudor).

- Lord Thomas Stanley (and his brother, William). Their army of c.5,000 men would hold the key to how the battle turned out, though at first, it was not clear on whose side they would fight. William had been a staunch Yorkist and supporter of Edward IV and his brother, Richard III. But Thomas liked to see which way the tide was turning before committing his soldiers. His arse must have been riddled with splinters from his inveterate fence-sitting. Two further complicating factors were that Thomas had married Lady Margaret Beaufort (Henry Tudor’s mother) and King Richard, mistrusting the Stanleys, had taken Thomas’ son (Lord Strange) hostage to ensure his loyalty on pain of (his son’s) death.

3. Richard III may have been undone by treachery in his own ranks.

In the early phases of the battle, Richard’s vanguard was engaged in fierce hand to hand fighting with Oxford’s men. Proving the steadier, the latter began to push Norfolk’s battle back, with a good number choosing to flee at that point.

Seeing this, Richard called for Northumberland to move up in support, but Lord Percy failed to respond, leaving his men where they were.

Historians have long debated whether Percy had chosen to desert the king’s cause at that point, or whether it was simply that the marshy ground prevented him from manoeuvring into position. To this day there is no consensus on this point, but it cannot be doubted that Percy’s inactivity played a major role in the outcome.

4. Free Pub Quiz Points

Richard III was the last of England’s monarchs to die in battle.

The last monarch to lead his troops into battle, however, was George II when he commanded the allied forces fighting the French at Dettingen in 1743.

There you go: two easy marks at your next pub quiz. Thank me later.

5. Richard came within a gnat’s whisker of winning

As the battle wore on, it became clear (to Henry at least) that Richard’s superior numbers would likely be decisive in the end. It is thought, therefore, that he took a huge gamble by making a move towards the Stanley forces, presumably to implore them to join the fight on his side before it was too late.

Seeing that Henry was now separated from his main army, with only his closest followers and some French mercenaries for protection, Richard chose that moment to launch his own massively risky throw of the dice. Sources are unclear as to whether he rode with 800-1000 knights or just his own household men, but the king led a cavalry charge aimed directly at Tudor.

To show how close he came to success, Richard managed to kill Henry’s standard bearer, Sir William Brandon, with his lance (as well as unseat Sir John Cheyne). When you consider that the job of the standard bearer was to stay next to their lord (so that all could see where he was and that he was still alive), you can hopefully have some idea of Richard’s proximity to Henry at that moment. Fortunately for Tudor, however, his French mercenaries and household troops were able to shield him from danger. In that moment, was the battle lost rather than won.

6. Did Richard deliberately target the Standard bearer?

It’s an interesting point. As mentioned above, the purpose of the standard was to tell everyone where the owner stood (to act as a rallying point) and also to show he was still in the game. It may be that, by targeting Sir William Brandon, Richard hoped to demoralise Henry’s army when they saw the banner fall.

To my mind. I am not entirely convinced; killing Henry would surely be the more likely way to secure victory (news of his death would soon spread). Also, with Brandon dead, it would not be long before someone else grabbed the standard from his cold, lifeless fingers and raised it again.

7. Who was braver? Richard or Henry.

Most people will be aware of how Shakespeare chose to portray Richard in his play. Combined with other subsequent, overt Tudor propaganda, you could be forgiven for thinking that he was a snivelling, hunchbacked weasel who murdered his young nephews so he could steal the throne.

I’m not going to comment on the latter (I know what I think, but some people do tend to get upset about these things…) but in reality, Richard was a competent king and a courageous fighter (in spite of the scoliosis (curvature of the spine) which was so wonderfully confirmed when his bones were found in Leicester). He’d fought in a few battles before 1485 – beginning as a teenager fighting for his brother, King Edward IV – and not once did he disgrace himself. The charge he took part in mentioned above would not have been out of character.

Henry, however, had never fought a battle and did not engage in the fighting at Bosworth. After Richard’s attack, he was quickly surrounded by his bodyguard and shepherded to safety. There is even the suggestion that he dismounted to better conceal himself amongst his men at arms. Note: that’s not to say Henry was not a great king (he was!). Just that his mind was more suited to commerce and diplomacy than the more martial skills. He must have been incredibly pissed off that the stable, reorganised system of government and full coffers that he left to his heir were soon spaffed up the wall by his narcissistic, bullying ingrate of a son (Henry VIII in case that was not clear).

8. The Stanleys to the rescue? But for whom?

Although Richard had failed in his daring attempt to kill Henry Tudor, all was not yet lost if only the Stanleys could be persuaded to join the fray on the king’s side. And it was at that moment of Richard’s greatest need – while he was closely entangled with Henry’s men – that Lord William Stanley made his move.

Unfortunately for Richard, however, Stanley rode to Henry’s aid. Perhaps, he was acting on the orders of his older brother who – being Henry’s stepfather – had decided not to annoy Margaret Beaufort. Happy wife, happy life… am I right?

Quite what hostage, Lord Strange, thought of that decision is not recorded. Though, as he didn’t get killed he probably decided to quit while he was ahead. After all, it wouldn’t pay to annoy dad by criticising his new, younger wife.

9. The Battle of Bosworth marked the end of the Wars of the Roses

This period of civil war between the Houses of York and Lancaster had begun with a battle in the streets of St Albans in 1455. Whilst the Battle of Bosworth Field was certainly the last major conflict of the war, it cannot be said to mark the actual end. The battle of Stoke Field took place in 1487, in which the Yorkists tried (and failed) to oust King Henry VII in favour of the supposed pretender, Lambert Simnel. It actually took Henry many years – with further Yorkist-inspired pretenders and rebellions – before he could feel secure.

10. Our new dog is named for this battle

This is half true. He’s a rescue dog from Bosnia, so Boz was a clear winner as a name and suits his nature down to the ground. However, I did manage to ensure that his full – or Sunday – name is Bosworth (that’s how he’s registered at the vets anyway).

Leave a comment