Note: all images in this blog are public domain.

In book 3 of my Rebellion Trilogy (The Reckoning – due out later in 2025), a new character comes into play, albeit by proxy as he remains ‘off stage’ throughout the whole book. King Maol Chaluim mac Dhonnchaidh or, as he is more commonly rendered in English, King Malcom III (nicknamed, Canmore which, in Scots Gaelic, means ‘big head’).

Note: Big Head should be interpreted as ‘great chief’ rather than thinking Malcolm had to duck every time he entered the room.

Though he features only in passing, he is – historically speaking – a hugely important figure in terms of the future line of succession of the monarchs of England (right down to the present day), along with the unification of Saxon and Norman blood lines.

What’s that? You want to know more? Ok then.

Before we can talk about King Malcolm’s role in uniting the two bloodlines, we need to drop back in time to 1016. In that year, the Danish King Knut (he who supposedly tried to stop the waves, although not in order to demonstrate his power, but rather his lack of it before God) acceded to the throne of England following the death of King Edmund Ironside (still the coolest moniker ever for any monarch of England).

Knut had fought Edmund at least four times in 1016, with neither Danes or English achieving a decisive victory. In the end, a peace treaty was signed in October which effectively split England into two (the north and eastern portion to be ruled by Knut). Within a month, however, Edmund was dead; possibly from wounds sustained in battle. That said, whilst there is no evidence of foul play, rumours persist that someone shoved a spear up his backside while he was sat on the loo. Definitely not cricket, what?

With only his two infant sons to succeed Edmund, there was now nothing to stop Knut from taking the throne. Unsurprisingly, one of the Dane’s first kingly acts was to deal with the threat of Edmund’s boys. Rather than kill them himself (a la Richard III #bait), however, he sent them to the King of Sweden (with instructions for them to be done away with). The kids proved to be too damned cute to kill, though; either that or the Swedish queen told her husband that he better not dare harm them. To cut a long story short, they ended up at the court of the Rus king in Kyiv, where they grew up in the company of a number of other princely exiles.

Details of their (Edward and Edmund) lives over the following decades are sparse. Suffice to say that Edward (known as The Exile) is later found in Hungary, having supported Prince Andrew’s bid for that throne in the 1040s (Andrew had been another exile in Kyiv), while Edmund disappears from the record – perhaps killed in the fighting.

It was while he was there (c.1046) that Edward the Exile took a wife (Agatha) with whom he was to have three children (all born in Hungary): Margaret, Cristina and Edgar.

Note: Agatha’s lineage is uncertain and the subject of much speculation. Several sources describe her as a kinswoman of (Holy Roman) Emperor Henry II, so Edward was definitely ‘punching’.

Claim to the throne of England

Many of you will be aware of the competition for the throne of England following the death of Edward the Confessor in January 1066. On the one hand, William, Duke of Normandy, was adamant that he had been promised the crown by his kinsman (in-law) back in 1051, and that Harold himself had sworn an oath to support his claim when he visited Normandy in 1064/5.

On the other hand, we have Harold who was elected by the Witan and who swore that Edward had promised him the throne with his dying words.

Note: for those who have watched King & Conqueror (K&C), firstly… well done! It’s quite a struggle to endure. One of the few things I did like, though, was how they portrayed this scene… “What’s that, your Majesty? You want me to be king?”

There was a little-known third option, though (strangely omitted by K&C). By the mid-1050s, it was pretty obvious that King Edward was not going to father an heir (not least because of the rumours that he had refused to consummate his marriage to Harold’s sister, Edith (not Gunnhild as K&C randomly decided to name her!).

It was around this time that King Edward became aware of Edward the Exile’s existence in Hungary (he would naturally have assumed his infant nephews had been murdered 40 years earlier on Knut’s orders). Envoys were dispatched to Hungary to secure the Exile’s return: the throne of England awaited him. For me, the Hungaro-English Aetheling (literally: throne-worthy one) would have been the Confessor’s preferred choice to succeed. A proven warrior in his 40s (sound like anyone else…? <cough – Harold – cough>).

But, like a medieval Eastenders, no one saw the twist coming. Within days of Edward the Exile having landed in England in 1057 (and what a strange experience that must have been – heir to the throne but probably not speaking a word of English other than: ‘Which platform is the train to London?’ or ‘Where are the toilets, please?’), he was dead. He didn’t even get to meet his uncle. None of the sources mention foul play, though it cannot, of course, be ruled out. Equally, he may just have caught a dose of man-flu. (As my wife knows only too well, the English variety can be near fatal. Even today.)

Although things were now looking a little bleak for the dead prince, all was not lost for The Confessor. Hearing of his nephew’s death, he would have ‘simply’ switched his hopes and support from the Exile to his son, Edgar (known to history as Edgar the Aetheling). At this time, Edgar (possibly born c.1052) would have been about 5 years old. Way too young to be king, but then Edward had no plans to die for ages yet.

The king actually lived on for another 9 years, before succumbing to illness in January 1066 (Edgar would now have been around 14). In more peaceful times, and without an opportunistic, overmighty earl waiting in the wings, Edgar might well have been elected king. As it was, the hugely wealthy, proven general, Harold Godwineson, was chosen by the Witan to succeed the Confessor. In hindsight, it was probably the right decision in the circumstances (the threat-level dial was turned to exceptional after all). Objectively speaking, however, the lad woz robbed. Absolutely done up like a kipper.

Fast forward ten months and King Harold is now dead, having been killed by and replaced by William of Normandy.

Note: Edgar was actually proclaimed king in the wake of the Battle of Hastings, but he lacked the support to make it stick and had to submit to William after a few weeks. Make a note to try that argument the next time your local pub quiz asks how many kings of England were there in 1066? Answer: 4 (not 3). The fact that Edgar was never crowned did not matter under Saxon laws.

King William was beset with rebellions for the first years of his reign, a fair few of which involved Edgar – especially those in the north of the country (see my novels for details). But when things became a little too hot for his liking in c.1069, Edgar sought refuge with the Scots, where he was welcomed at the Dunkeld court of King Malcolm Canmore III (finally, he’s back in this story!). It was also there that he was reunited with his mother and two sisters, who had fled north, a year or too earlier.

Now this is where things become interesting (who said: ‘At last’? Was that you, Frobisher? See me after school).

The Scottish Play, er… Marriage

By 1068, it is not clear whether Malcolm’s first wife, Ingibiorg Finnsdottir, had died or whether she was put aside. Either way, the presence of Edgar’s sisters was too good an opportunity for the Scots king to miss as they were both of significantly higher status (and therefore political influence) than Ingibiorg. The sad fact is that if a niece of the previous, childless, King of England suddenly comes on the market, you trade in your old model, no questions asked. Pack your bags, Ingibiorg, it’s off to the convent with you.

And this is exactly what Malcolm did when he married the elder of the two sisters, Margaret. Edgar would have provided his assent for the match (in place of his father); there is no doubt that the match was in his interests. The chance to invade England with a Scots army at his back would definitely have had him rubbing his hands with glee.

The wedding was a direct threat to King William. It would not have escaped his notice that the couple eschewed traditional Scottish names for their four sons and instead chose: Edward, Edmund, Aethelraed and Edgar. Every one of them was a direct relative of Margaret’s from the royal house of Wessex. They might as well have named them: Dude, your days, are numbered, chum. It was that clear a message to King William.

However, it was not the sons who were to effect a seismic change in the bloodline of the English royal family. That role fell, some years later, to Malcolm and Margaret’s eldest daughter, whose birth name was Edith (yet another nod to the Wessex line).

Born c.1080, Edith was educated in England in a series of convents (at least one of which was under the control of her aunt, Cristina). During that time, she never took the veil, having no desire to become a nun.

In August 1100, Henry I (4th and youngest son of The Conqueror), came knocking. At that time, the new king was desperate to legitimise his rule in England in the face of a significant challenge from his older brother, Robert Curthose (who was the current Duke of Normandy), as well as the persistent whispers about his possible involvement in the death of his other brother, King William II (Rufus) of England, killed by an arrow in the New Forest in an apparent ‘hunting accident’.

Marriage to Edith (who now assumed the more acceptable (to Henry) Norman name of Matilda) was the cornerstone of Henry’s royal manifesto which was centred around the correction of abuses perpetrated by his brother and father, together with a return to the more gentle times of Edward the Confessor.

As a close relative of Edward the Confessor, Matilda was ideally placed to help cement this rapprochement between the English and Norman factions, by bringing together the two bloodlines (much like Henry VII did when he married Elizabeth of York in the 1480s). Any children they would have would carry the blood of both ‘sides’, making them true Anglo-Norman monarchs.

It is from this point, that all the future monarchs of England can claim descent.

Postscript

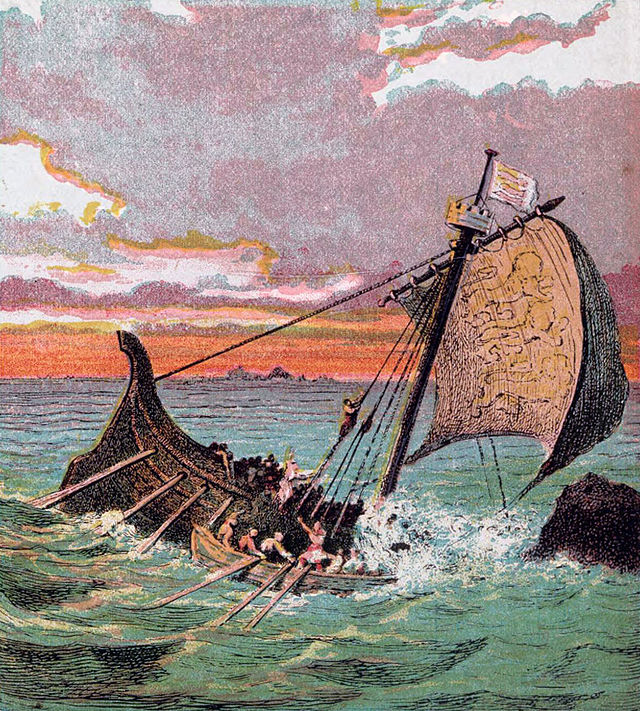

Although Henry and Matilda had two children (Matilda – a hugely unoriginal choice – and William – not much better to be honest), securing the succession was not to be plain sailing (niche joke – award yourself 2 points if you got it). Henry’s only son, William Adelin (i.e. Aetheling) was to die in the White Ship tragedy in 1120 while 17 years old, leaving Matilda as his only legitimate heir.(It’s ironic that Henry fathered some 22 illegitimate children – a record for a monarch of England at time of going to press).

Although the barons of England swore to Henry that they would support Matilda’s rule, they quickly reneged on that deal when the old king died (of a ‘surfeit of lampreys’ – look it up; sounds disgusting!). Despite their fine promises, they weren’t quite ready to have a female boss. Cue 19 years of brutal civil war (called, tellingly, The Anarchy), from which Matilda’s son – Henry II – eventually emerged to claim the throne. And the rest, as they say, is history.

So, although the Norman Conquest effectively eviscerated the Anglo-Saxon nobility, they were down but not out. But it needed a woman – Saint Margaret of Scotland – to put them back on their perch.

Leave a comment