Images all public domain unless otherwise stated.

A mother, a warrior, a builder, a diplomat. In fact, a queen in all but name, without whom the foundation of what we now know as England might very well have floundered. So why is it that Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, lurks in the shadows in comparison to her more famous father, brother and nephew? For too long her critical role in this nation’s formation has been overlooked or underplayed.

That Henry of Huntingdon wrote in the 12th century that she was “so powerful that in praise and exaltation of her wonderful gifts, some call her not only lady, but even king” goes some way to explain her lack of profile. She was a woman in what was then a man’s world and the fact that she was absolutely killing it despite her gender, led to her being compared to a man, rather than lauded as a woman.

Who was Aethelflaed?

She was the daughter and eldest child of King Alfred the Great (of Wessex) and his Mercian wife, Eahlswith. We cannot be certain of when she was born, but 869/870 is a reasonable guestimate, not least because her parents had married in 868.

She was also the sister of the future King of Wessex (and a bit more), Edward the Elder, and thus aunt of the future, first king of England, Aethelstan. A rich pedigree indeed.

Side note: The ‘Elder’ soubriquet was a later addition, when it was needed to distinguish him from his great grandson who ruled from 975-80.

Early Life

Not much is known about Aethelflaed’s early life, and what we do know is derived largely from chronicles associated with her father. An excellent role model, King Alfred set as much store by learning and culture as he did the more martial skills. As such, it is believed that – unusually for the time – Aethelflaed received the same education as her brothers. Surely, one of the key factors that helps explain her future development into the brilliantly effective ruler she would one day become.

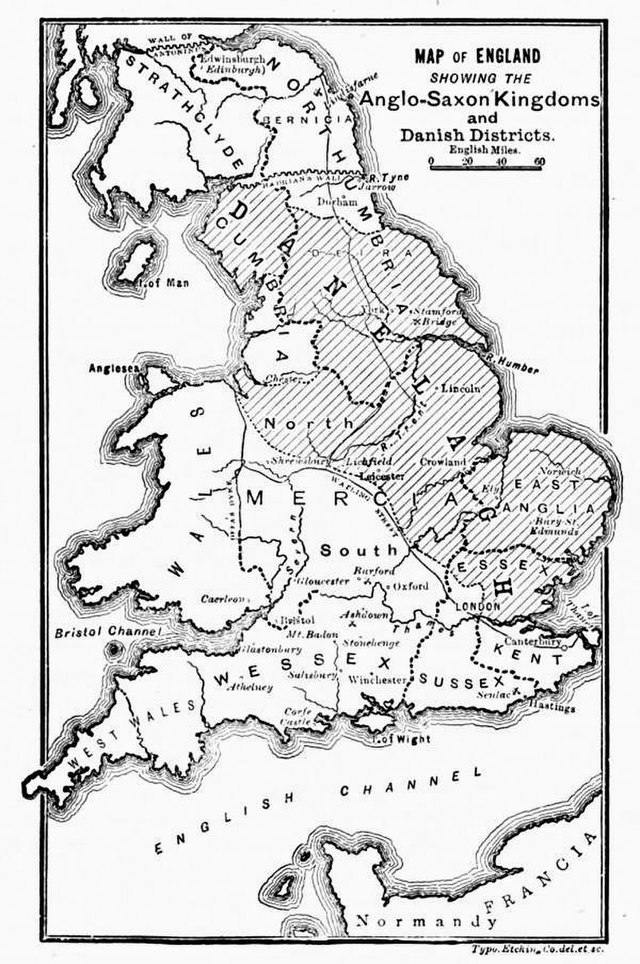

Another key factor would have been the impact of her childhood experience, witnessing her father’s desperate fight for the survival of his kingdom against the Great Heathen Army, especially in the period from her birth to May 878 when her father won the crucial Battle of Ethandun (Eddington). From that time on, Wessex was largely safe, though England itself was effectively split into two: the south and the western part of Mercia for the Anglo-Saxons, and the north and eastern half of Mercia (and also East Anglia) under the ‘Danelaw’.

Just four months earlier in January, Wessex had been on the brink of collapse when the pagan Vikings overran the royal palace at Chippenham, Wiltshire, where Alfred, his family, and his closest followers had been celebrating Christmas. By good fortune, the king managed to escape into the marshes of Somerset around Athelney a small number of followers. There, he set about rebuilding his strength from what must have seemed an almost hopeless position.

Assuming Aethelflaed was with him in those marshes, she would have seen and learned firsthand, some hugely value lessons on what it took to be a successful leader of men in the face of massive adversity.

Peaceweaver

The word ‘peaceweaver’ was used to describe one of the most significant roles that a royal woman might play – i.e. to be married to a king or other significant noble in order to seal an alliance or, in other words, to weave peace between two parties.

So it was that Aethelflaed’s first proper appearance in the record as an adult was when Alfred, in 886, offered her in marriage to his loyal supporter, Ealdorman Aethelred, Lord of Mercia. She would have been around 16 at that point with her husband probably similar to her father’s age.

This could have been the point at which nothing much more was heard of Aethelflaed, other than perhaps recording her death or her retirement to take up holy orders. But no daughter of Alfred was about to fade into the shadows.

She was soon to be found taking an active role in government alongside, and also instead of, her husband. In part, this was driven by necessity because it is generally accepted that Ealdorman Aethelred was suffering from some sort of debilitating illness that kept him sidelined for significant periods of time from c.902 to his eventual death in 911.

The enforced need to take a more prominent role allowed her to display her shrewd leadership capabilities in terms of strategy, diplomacy and driving the refurbishment and strengthening of towns. As just one example, when she granted lands on the Wirral for a band of Norse exiles from Dublin to settle, she also refortified nearby Chester’s Roman walls… just in case. Her caution was rewarded in 907 when, as she had suspected they might, the Norse grew restless and launched an attack on the city. They failed to breach its improved defences.

Lady of the Mercians

When her husband died, the senior nobles in Mercia, the Ealdormen, took the extraordinary, but wholly understandable, step of declaring Aethelflaed to be sole ruler with the title: Lady of the Mercians. Back in Wessex, a woman had never reached such heights; her mother – Alfred’s ‘queen’ was only ever referred to as ‘wife of the king’ and never witnessed a charter, but in Mercia – where there was a stronger tradition of women holding positions of influence – no such scruples existed. Their only concern was to do what was right for Mercia.

What were her achievements?

Militarily: she secured a number of important victories during her time as ruler of the Mercians, thereby founding and embedding her legacy as a warrior queen. The battle of Woden’s Field in 910 (likely to be Wednesfield near Tettenhall) stands out, as does her later capture of Derby (the centre of one of the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw) in 917.

Diplomacy: From Derby she next took Leicester and was soon moving towards York – the centre of Viking power in England. It is recorded that the Danes were ready to submit to her overlordship, an amazing achievement which was only thwarted by her unexpected death in June 918.

She also understood the need to work with Wessex, and particularly with her brother, King Edward. On their own, they would have likely been no match for the Danes, but together they had the joint vision and the strength to push the Vikings back so that, by the time of her death, all England south of the Humber was under the control of either Mercia or Wessex. Thus was the foundation secured for Aethelflaed’s nephew, Aethelstan, to become the first monarch of something we would today recognise as England.

Strategically: She continued the work her father had begun in creating burhs (i.e. fortified towns) across her dominions. These burhs acted partly as defensive centres from which to resist Danish incursions, but also as forward bases from which new campaigns could be launched into the Danelaw. Each time gains were made, Aethelflaed was quick to ensure they were secured by erecting a new burh. Places like Runcorn, Tamworth, Stafford, Warwick and Gloucester owe their prominence to her, having either been created by her or had their existing fortifications strengthened by her.

Sidenote: to learn more about this defensive network, please check out my previous article.

Aethelflaed took pains to invest heavily in churches, recognising the need for her people to believe they had divine favour in support of the fight against the pagan Danes. In Gloucester, especially, she created an important new town whose prestige she then bolstered hugely by translating the relics of the 7th century warrior saint, King Oswald, from Viking-held Bardney in Lincolnshire to a church that she ordered to be built. The pomp and circumstance that would have greeted the return of this celebrated figure’s remains would have added massively to her reputation and renown.

Note: it was in her church in Gloucester – St Oswald’s Priory – that Aethelflaed would come to be buried.

State-craft: as well as supporting urban regeneration, educational programs via monasteries and patronage of the arts, Aethelflaed also went about securing her legacy by ensuring that her only child (a daughter called Aelfwynn) would succeed her. In doing this, Aethelflaed was doubly unique: she was the first woman to rule an Anglo-Saxon kingdom and – even more extraordinarily – the first woman to pass on power securely to another woman.

She also took responsibility for the upbringing of King Edward’s first-born son, Aethelstan. That he, too, would become such a strong and successful ruler must, at least in part, be down to the values, skills and education provided by his aunt.

Summary

Given her achievements at a time when women could not readily come to the fore, as well as under the incredibly difficult circumstances of the Viking threat, it is (in my humble opinion) hugely disappointing that Aethelflaed does not rank alongside other female role models who more easily come to mind as being household names. If you were to ask 100 people to name a strong female ruler from British history, our survey should say “Aethelflaed” just as much as Elizabeth I (or II for that matter), Victoria or Boudicca.

So why is she not more well known?

Something that immediately stands out is the extent to which she was written out of the main historical record of the time: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (ASC). Although it exists in a number of manuscripts, the composition of the ASC was almost exclusively in the hands of the West Saxons. And in view of the desire to promote a unified country, the degree to which Wessex and Mercia were separate entities had to be downplayed. The most effective way of doing this was to focus on the achievements of Edward the Elder to the detriment of his sister.

In fact, only one version of the ASC really gets to grips with Aethelflaed. This version contains something that is known as The Mercian Register which reveals far more detail from the perspective of that region (i.e. it was almost certainly being written in Mercia).

To add further grist to this mill, we can also look at what happened to Aethelflaed’s daughter after her mother’s death. Although the Mercian nobles willingly elected Aelfwynn to be the next Lady of the Mercians, she would last no longer than six months. Driven by his overarching ambition to rule a united ‘England’, Edward the Elder (who styled himself King of the Anglo-Saxons) took Mercia for himself, deposing his niece and sending her to Wessex, where she may well have entered a religious house for the rest of her life.

Sidenote: Aethelflaed only gave birth to one child. Whether it was fear of the huge risks involved in childbirth, an exceptionally difficult pregnancy (which may have prevented her from conceiving again), or a combination thereof, William of Malmesbury wrote that she declined to have sex after Aelfwynn’s birth.

Although Aethelflaed’s name continued to resonate (not least – perhaps incongruously – among the Normans whose chroniclers admired her military achievements), the death knell for her renown was to come under the reign of Elizabeth I. Good Queen Bess identified more closely with Boudicca – perhaps because of their shared red hair – meaning that the memory of the Saxon warrior queen became ever fainter.

Until, that is, 1913 when the good burghers of Tamworth erected a statue in her honour (showing her holding a sword and with her other arm around the shoulder of her young ward and nephew, Aethelstan.

Since then, she has slowly worked her way back into the nation’s consciousness, as seen by a respectful treatment and portrayal in the recent TV series The Last Kingdom based on Bernard Cornwell’s novels. Hopefully, yet more time will see her elevated to her rightful place among the great rulers of Britain.

Leave a comment