In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (specifically the Winchester Manuscript, also known as version [A]), the entry for the year 925 [924] reads as follows:

“Here, King Edward [The Elder] passed away, and Æthelstan, his son, succeeded to the kingdom.”

Taken at face value, one might be forgiven for thinking that the transition of power from one to the other was swift and uneventful. Just as night follows day, so too the crown passed from father to eldest son. No dramas, no problems. Move along there – there’s nothing to see here, right?

But probe a little more deeply into the sources and another story emerges. One in which Æthelstan’s succession to the throne of Wessex – and his eventual path to becoming the first king of something we would now recognise as England – was anything but a foregone conclusion.

The first clue we find that something might not be right seems innocuous at first glance. King Edward died in July 924, yet Æthelstan was not crowned until September 925. Whilst coronations were not always immediate (at that time, it was acclamation by the Witan (the king’s council) that conferred kingship, rather than the Latin prayers and mumblings of a bishop or three), such a long gap is remarkable.

It is also worth noting that, prior to 1066, succession by the eldest son was not a certainty. Æthelstan’s own grandfather – King Alfred the Great – was a recent example of this. Alfred had been the youngest of five brothers, and thus very unlikely to succeed. But in 871, his chance came when his last remaining brother, King Æthelred, died.

Even though Æthelred had two sons (Æthelhelm and Æthelwold), the crown still passed to their uncle. In this case, it was more important that there be a proven general at the helm to continue the fight against the Great Heathen Army which was still ravaging the country. Alfred was simply the best choice in the circumstances – certainly more so than untested youngsters.

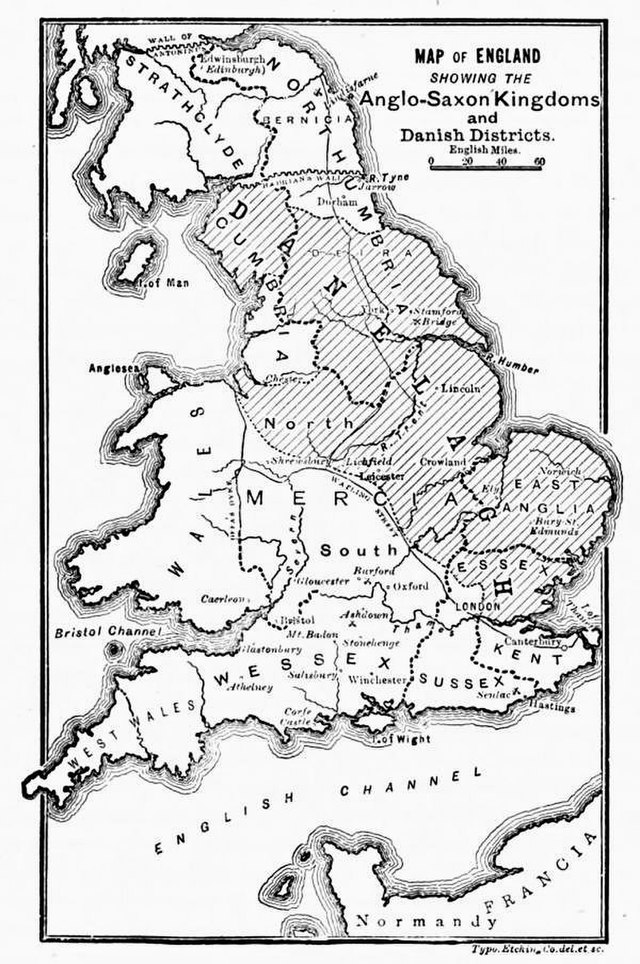

So, having established that primogeniture was not a definitive custom at this time, what of Æthelstan’s situation? At the time of his father’s death, he was roughly thirty years of age. For more than a decade, he’d been cutting his teeth as a war-leader in the ongoing campaign to rid Mercia of Danish invaders. First alongside his aunt – Æthelflæd – at whose court he had been brought up for many years and then – after her death in 918 – as de facto leader of Mercia, often fighting alongside his father’s warriors.

He was the right age. He knew how to lead men and win a battle. He was well educated and had been groomed for every aspect of kingship for many years. So, what was going on behind the bland words of the monks in Winchester in that short Chronicle entry? Why did it take more than a year for Æthelstan to be crowned?

An answer may be found in the thorny issue of dynastic politics. Æthelstan’s mother – King Edward’s first wife – was a noble woman by the name of Ecgwynn. Little is known of her origins, but it is tempting to suggest that she may have lacked the status supposedly required of a West Saxon queen; perhaps she brought little of tangible value to Edward, a man who might need to marry wealth and power to secure his hold on the throne in the event of a threat from rival claimants – such as his cousins referred to above.

Note: There may be an interesting parallel here with King Edward’s later namesake (the IV) who married a woman of lower station with whom he was said to be infatuated. But whereas Edward IV remained married to Elizabeth Woodville, Edward the Elder did not keep faith with Ecgwynn.

No sooner had Edward acceded to Alfred’s throne, than a rebellion broke out. His cousin, Æthelwold, so long overlooked for the crown he thought was rightfully his, saw an opportunity to seize power before the new king could fully establish himself. Although he failed in his bid for the throne, the fact that he then fled to York, where he was accepted as king by the Danes, made him an altogether more dangerous threat.

Edward’s response was swift. He moved to shore up his position by taking a new wife, one who probably hailed from a more thoroughbred lineage than Ecgwynn. In a move born of necessity, his first wife had to go – put aside in favour of more pressing dynastic concerns.

Edward’s new wife was called Ælfflæd. Again, little is known of her other than the fact that her father was called Æthelhelm. Though some historians have suggested that Æthelhelm might have been an ealdorman from a West Saxon shire, there is a case to be made for him being Edward’s cousin, the son of Alfred’s older brother, King Æthelred. With a royal pedigree, it would be a match as strong as Edward could make and the offspring of such a marriage would therefore be doubly royal.

Note: This supposition is shrouded in doubt in that it would have breached papal rules of consanguinity for Edward to marry his cousin’s daughter.

More importantly, though, setting Ecgwynn aside also put Æthelstan’s position in doubt. With no mother to protect the boy – not much older than a toddler at this time – and with Ælfflaed keen to use her newfound influence to protect the interests of any future sons that she might bear, there was little hope that Æthelstan might remain close by his father’s side.

And so, it proved. As soon as Ælfflæd’s first son was born, his half-brother’s demotion in status was almost immediate. From document evidence, we can see that the new child, Ælfweard, was witnessing charters (even though still a baby) and his name was listed immediately after that of his father. Æthelstan, although still a witness, was pushed further down the pecking order. The implication could not have been starker.

If further proof is needed, Æthelstan was soon packed off to the court of his aunt Æthelflæd (Edward’s sister), in Mercia. Outwardly, there was some sense to this move: i.e. fostering was noy necessarily unusual and where else might be acquire such a good grounding in the arts of ruling and war. Nevertheless, you can’t imagine Queen Ælfflæd being too upset at the prospect of her stepson leaving Wessex (it may well have been her idea). It removed one key barrier to her son’s prospects.

Quite what King Edward made of it is unclear. As long as he had sons to succeed him, his throne would be secure; the order in which they were born was less of an issue. That said, he would have undoubtedly been aware that a son born while he was king (i.e. Ælfweard) would have had a stronger cachet than one who was not (i.e. Æthelstan).

And so it remained for twenty or so years, until one fateful day in July 924 when King Edward, apparently in Mercia (near Chester) to deal with a rebellion of disaffected Mercian nobles supported by Welsh factions, died. The cause of his death is unknown, but he would have been in his early fifties and so ‘natural causes’ is not unlikely. A wound received in battle is also not beyond the bounds of possibility. The location of his death – a royal vill called Farndon, just to the south of Chester – might also support that hypothesis if the king was taken there to recover after the battle.

That Æthelstan fought at his father’s side in this rebellion seems likely, which meant that he would have been on hand at the moment of his father’s death. The Worcester version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle then records that Æthelstan was declared king by the Mercian nobility, a fact that was to be greeted with dismay in Wessex once delivered by the rider who galloped south with news of the king’s demise.

Despite his birth, Æthelstan was still an outsider to the West Saxons. We cannot even be sure that he had ever returned to Wessex since his move to Mercia. For them, Edward’s second son – now just out of his teens – was a known quantity, having been groomed in Wessex to succeed his father. With the Mercians declaring for Æthelstan and the West Saxons for Ælfweard, the future security of the Anglo-Saxon speaking people hung in the balance. King Alfred’s vision for a united realm, fighting back against the Danes, was on the brink of collapse.

But then, the whole picture changed dramatically. Just sixteen days later, Ælfweard died at Oxford. Once again, no explanation is offered and – it should be said – no rumour of foul play ever gained any traction (though, in the circumstances, it cannot be ruled out even if only because his death was so incredibly convenient).

Presented with such an opportunity, Æthelstan lost no time in pressing his claim for the throne of Wessex.

Note: Though Ælfflæd did have another son – Edwin – he was as yet too young and insufficiently established to be able to rally support to his banner.

But resentment did not go away immediately. The Bishop of Winchester, for example, refused to witness the new king’s charters and there were whispers of a plot to seize Æthelstan and put out his eyes – thereby rendering him unfit to rule.

With so much ill-feeling, it is perhaps no wonder that the coronation was delayed for more than a year. Perhaps it took that long for Æthelstan to feel secure enough to proceed. But when he did, it was a coronation like no other. For one thing, it did not take place in Winchester as all other West Saxon ceremonies had. Rather, Æthelstan chose a location – Cyninges tun (Kingston-on-Thames) – that stood on the border between Wessex and Mercia. The message could not have been clearer.

Finally, it should be noted that Æthelstan never married and – consequently – never produced a legitimate heir. On his death the throne passed to his stepbrother, Eadmund (the son of Edward’s third wife – Edwin having tragically drowned at sea some years before). At a time when one of the king’s most important duties was to produce children to secure the future of the dynasty, such a decision is incredible. Perhaps it was the price he had to pay to secure West Saxon support; you can be king for your lifetime, but then we want it back.

Leave a comment