All images used are public domain

It’s June 1098 in northern Syria. Blisteringly hot and dry. After 9 months besieging – and finally capturing – the vast city of Antioch, the greatly depleted army of the First Crusade is exhausted and starving, reduced to eating their horses, boiled pieces of leather or plants. Even the undigested grain seeds found in horse manure are not wasted.

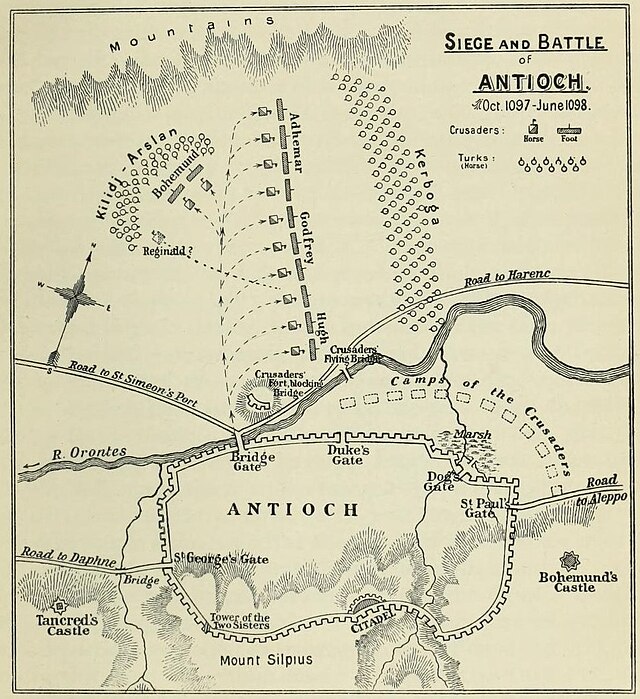

What’s worse is that not only has Antioch’s near impregnable citadel fortress managed to hold out, but they now find themselves besieged in turn by a huge relieving army of Turks (estimated to be at least four times as big as that of the Franks) under Kerbogha, regent of Mosul.

Things were looking desperate; death or surrender (also likely to result in death) were the only options left open to them.

But then on 28th June, the Crusaders sallied forth from Antioch and – defying all the odds – defeated Kerbogha’s vast forces. They were now free to continue on their way to Jerusalem.

What, then, lay behind this sudden, outrageous reversal of fortune?

The Holy Lance of Antioch

The classical version of events that has come down to us over the centuries was that the crusaders achieved their miraculous victory thanks to the Holy Lance which had recently been found within the St. Peter’s cathedral in Antioch.

But, whilst its impact can not be entirely dismissed, it is doubtful whether this provides us with the whole story.

What is the Holy Lance?

As many of you may know, the Holy Lance (a.k.a. Spear of Destiny) refers to the lance (or possibly pilum) that was thrust into Jesus Christ’s side while he was on the cross, to check whether he was still alive.

Of the four Gospels in the New Testament, only John mentions this:

One of the soldiers pierced his side with a lance (λόγχη), and immediately there came out blood and water.

– John 19:34

John does not, however, give us the name of the soldier. Rather, the oldest known reference comes from the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus (as part of a 4th century manuscript) which tells us that he was a centurion named Longinus).

So, at a time when religiosity played a much greater role in life, to possess such an important and holy relic would surely offer a morale boost of almost immeasurable proportions to a Christian army. In wargaming terms, this would be like throwing a 6 with the morale boost die, whilst also having a bonus score of +6.

The Battle of Antioch

This then brings us back to 1098 and Antioch. A couple of weeks after the arrival of Kerbogha’s troops, the Franks were close to collapse. Their numbers dwindling daily through combat, disease and starvation; their leadership at a loss as to what to do as well as being at odds with each other – it seems only a matter of time.

It was at precisely this point, however, that the story of the Holy Lance of Antioch begins. A miracle was needed and a ‘miracle’ was duly delivered.

Note: The Holy Lance of Antioch is not to be confused with the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch for which the instructions for use were recorded in the Book of Armaments:

First shalt thou take out the Holy Pin. Then, shalt thou count to three. No more. No less. Three shalt be the number thou shalt count, and the number of the counting shalt be three. Four shalt thou not count, nor either count thou two, excepting that thou then proceed to three. Five is right out. Once the number three, being the third number, be reached, then lobbest thou thy Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch towards thy foe, who, being naughty in My sight, shall snuff it.”

© Monty Python.

The Discovery

Step forward one Peter Bartholomew, a lowly peasant soldier (sometimes described as a priest or monk, but that is doubtful if not wholly incorrect) from southern France in the service of Count Raymond IV of Toulouse.

Peter came to Count Raymond, saying that he had been having visions from St Andrew for some months in which the saint showed him where the Holy Lance could be found (namely – and conveniently enough – in the cathedral of St Peter in Antioch). Peter and Raymond – assisted by a select group of 12 or so of Raymond’s men – then proceeded to lift the flag stones and began to dig.

By the end of the first day, a hole to the depth of two standing men had been excavated, but nothing had been found. Count Raymond had already left – perhaps now wishing to distance himself from his earlier enthusiastic support – and the rest were becoming disheartened.

It was then that Peter himself jumped down into the trench whereupon he was seen to produce a piece of iron from the soil which was immediately identified as the sacred lance head. To avert any misgivings, one of the witnesses claimed to have seen the metal protruding from the ground before Peter grasped it.

The chronicles then describe how the morale of the crusaders was so rejuvenated that they forgot all their ills and travails and sallied forth from the city to launch a surprise attack on Kerbogha’s massive army. With the Holy Lance being carried before the Franks, religious zeal carried the day; the Muslims were routed and large numbers of them slaughtered – apparently aided by visions of celestial knights on white horses, being led by St. George.

Analysis

It is easy to understand how this story – mostly recorded some time after the battle – gained traction. Deliverance from near certain destruction was proof beyond doubt that God favoured their endeavours. He had shown where the Lance could be found, enabling its use to then rally the troops to a glorious victory.

But, can we honestly say that this the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth? For the most part, I will leave that for the reader to decide, but allow me to offer some additional pointers to help illuminate your thinking.

Did they really find the Holy Lance?

It is, of course, impossible to say at this distance. They may have done, or they may have found what they believed to be a fragment of the Lance (this concept of ‘fragments’ of relics was already well established with the True Cross (a piece of which was already being carried before the army)).

What was not discussed, however, was that many of the Crusade’s leaders would have seen the Holy Lance that was already on display in Constantinople. Other sites also claim or claimed to have possession of the Lance, such as Vienna.

Note: If you will permit the levity, I can’t help but be reminded of the scene in Blackadder season 1, wherein Lord Percy Percy claims to have one of Jesus’ fingerbones, to which Baldrick expresses his disbelief because he thought they only came in packs of 10. (the sale of false relics was rife in the middle ages).

It was also very useful for Count Raymond’s political ambitions (especially in his power struggles with the other leaders), to have one of his own men to discover this piece of iron, even after a whole day’s fruitless digging.

The choice of Peter as the conduit for this miracle is also interesting. A drunkard womaniser of low social status doesn’t sound like the obvious choice to be a instrument of God.

In truth, however, my opinion on this event is that it doesn’t really matter who found or planted what. What mattered was that the leaders of the Crusade found a way to make use of the ‘relic’ to give heart to the rank and file soldiers and – more importantly – that the latter believed they were being led into battle by the Holy Lance.

What effect did the Lance have?

Was it really the Lance inspired the Crusaders to victory? Though this is what the chronicles would have us believe, there are other, less well known, sources that provide alternative ideas.

The Lance was found on June 14/15th, but the attack did not happen until June 28th. In that desperate, febrile atmosphere and with such an apparently huge fillip to the army’s morale, why then wait almost two weeks before acting? Two weeks in which you might expect to lose many more men to starvation, disease and injury. If it were you or me (and I’m very pleased it wasn’t), we’d be grabbing the lance, jumping on our (hopefully uneaten) trusty steed and shouting: “Follow me, Boys. Death or glory”.

Instead, other sources suggest that in those intervening days, the Crusaders tried to negotiate some form of surrender. One suggestion was that, to save lives, one hundred men from each side should fight it out: winner takes all. To me, this suggests that, even with the Lance, the Crusaders still lacked confidence in their ability to escape, let alone defeat Kerbogha.

Note: Kerbogha was no fool. He quite rightly rejected the idea of the 100-a-side Royal Rumble; why on earth would he surrender his huge numerical advantage?

Kerbogha rejected their overtures, demanding their unconditional surrender. Now the Franks knew they had but one option left (other than ignominious, and probably fatal, capitulation).

How then, did they win?

I’m no military strategist but it would not be the first, or indeed last, time that a numerically inferior force of heavily armoured Frankish knights supported by similarly equipped men at arms would defeat a Muslim army.

That critical advantage, combined with Kerbogha’s nervousness and miscalculation, provided the setting for the Crusader’s victory. I have no doubt that the army was bolstered by the presence of the Lance, but Kerbogha’s refusal to listen to advice was most likely the main reason for his undoing. Urged to attack as the hungry, ramshackle Crusaders emerged from the city, he elected to wait.

It soon became apparent that he had underestimated the size of the Frankish force (and perhaps also overestimated their parlous state). He tried to use the familiar tactic of drawing the knights on into less favourable ground, whilst also pelting them with arrows from his horse archers, but Bohemond of Taranto (leading the Crusader army) was ready for this.

Soon, panic began to spread amongst the Turks. As the expected victory grew less and less likely, one by one the Emirs deserted Kerbogha until the whole army was in disarray and fleeing in all directions, pursued by the avenging angels of St Geroge, St Mercurius and Saint Demetrius.

Footnote: What became of Peter Bartholomew?

Perhaps in part due to his lowly status, Peter was always subjected to doubt from many of the nobles who refused to believe his tale.

Finally, in an attempt to salvage his reputation, he volunteered to undergo an ordeal by fire in April 1099, a feat that ultimately led to his death. He claimed that he had been unharmed by the flames and that his injuries were the result of subsequent jostling by the crowd of onlookers, but it is generally accepted that he was hideously burned beyond any hope of recovery.

Leave a comment